RamistThomist

Puritanboard Clerk

Beaney, Michael. Analytic Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2017.

This is not merely an introduction to analytic philosophy. It is a fine introduction to modern philosophy, even to philosophy as a whole, in general. Because of the highly technical nature of analytic philosophy, this review cannot cover everything in the book. Some important matters, such as Russell’s “Set Paradox,” will have to be omitted.

Things and Kinds of Things

We begin with Gottlob Frege. If someone asks the question, “How many things are in the universe?”, how would you answer? Admittedly, it is impossible to answer, but it does illustrate a point. We can explain by a simpler example. If I show you a book, how many things am I showing you? Let us say the book has 150 pages. We attribute the number 150 not to the book itself, but to the concept “page of this book.” This concept has 150 instances (Beaney 9). For Frege, “number statements are assertions about concepts.” More specifically, a concept is “a property of a thing” (10). The “property of x” is a logical property.

Not only do we have “things” and “kinds of things,” but Kinds of things can be divided into objects and concepts. An object falls under a concept. A first-level concept is that under which an object falls. The second-level concept is one that falls within a first-level concept (11). For Frege, a number statement states that a first-level concept falls within a second level concept, and a second level concept instantiates a certain number of instances to the first-level concept.

Example: This book has 150 pages.

Translation: “The first level concept ‘page of this book’ falls within the second-level concept ‘has 150 instances” (11).

Moving on, a class or set is an extension of a concept (12).

How Can We Speak of What Does Not Exist?

Problem: Unicorns are one-horned animals.

Existential Statements

We know that unicorns, for example, do not exist. But they do exist in our minds, so what do we do with the word “exist?” Remembering Frege’s claim that “number statements are assertions about concepts,” we need new tools to express that (26ff). They are universal and existential quantifiers, noted thus:

“Unicorns do not exist”

Becomes

– (∃x) Ux

Which Beaney explains to mean, “It is not the case that there are some unicorns.” Therefore, “When we make an existential claim, then, we are not attributing a first-level concept to an object, but a second level concept to a first-level concept” (27).

Applied to theology, this means the ontological argument is unsound. An existential claim is an instantiation of concepts, not objects. God, a first-level concept, can be (and should be) defined as exemplifying all the great-making properties.But is this the same thing as exemplifying existence?

Beaney gives a simpler explanation. If I say “the class of unicorns is a subset of the class of animals,” am I saying unicorns really exist? No, “for are talking about (ultimately) about concepts, not classes” (37). What we mean, phrased in quantificational logic, is

(∀x) (Hx → Ax)

“For all x, if x is a unicorn, then x is an animal.” In other words, anything that falls under the concept unicorn falls under the concept animal.”

Do You Know What I Mean?

Sense and Reference

Hesperus is Phosphorus.

Both of these, one the evening star.and one the morning, refer to the planet Venus, but in different senses.

Evaluation

I am skipping the section on Wittgenstein and language-games, important as it is. That (probably) deserves and has its own book. Rather, I will spend some time analyzing Beaney’s take on the analytic-continental divide.

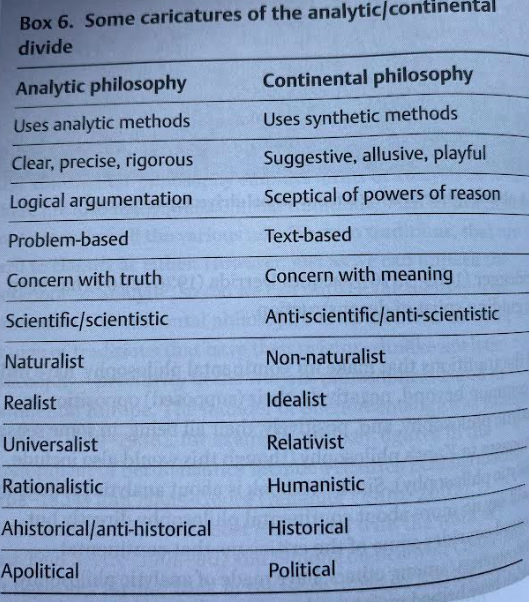

As students of philosophy today are grudgingly admitting, the divide between analytic and continental styles is not airtight. True, but it is still there. It is certainly the case that analytics aim for precision while continentals tend to reduce things to metaphors and “play.” That said, analytics are often very reluctant to explain modal and symbolic logic.

The next row is certainly accurate. Continentals, most notoriously with John Caputo’s claim that logic was a white man’s enterprise, are skeptical of reason.

The realist/idealist paradigm is odd. If by “realist” Beaney means focused on a real, external world, he is correct. If he means Platonic realism, which I do not think he does, he is incorrect.

The apolitical/political divide is certainly accurate, with exceptions. Bertrand Russell, for example, lobbied for numerous globalist fronts. Continentals, often taking their cues from Marx and French Communist radicals, are certainly more focused on politics.

Conclusion

I knew something about analytic philosophy before reading this book, having even read Frege. Beaney did a find job explaining all the parts I could not understand from Frege.

This is not merely an introduction to analytic philosophy. It is a fine introduction to modern philosophy, even to philosophy as a whole, in general. Because of the highly technical nature of analytic philosophy, this review cannot cover everything in the book. Some important matters, such as Russell’s “Set Paradox,” will have to be omitted.

Things and Kinds of Things

We begin with Gottlob Frege. If someone asks the question, “How many things are in the universe?”, how would you answer? Admittedly, it is impossible to answer, but it does illustrate a point. We can explain by a simpler example. If I show you a book, how many things am I showing you? Let us say the book has 150 pages. We attribute the number 150 not to the book itself, but to the concept “page of this book.” This concept has 150 instances (Beaney 9). For Frege, “number statements are assertions about concepts.” More specifically, a concept is “a property of a thing” (10). The “property of x” is a logical property.

Not only do we have “things” and “kinds of things,” but Kinds of things can be divided into objects and concepts. An object falls under a concept. A first-level concept is that under which an object falls. The second-level concept is one that falls within a first-level concept (11). For Frege, a number statement states that a first-level concept falls within a second level concept, and a second level concept instantiates a certain number of instances to the first-level concept.

Example: This book has 150 pages.

Translation: “The first level concept ‘page of this book’ falls within the second-level concept ‘has 150 instances” (11).

Moving on, a class or set is an extension of a concept (12).

How Can We Speak of What Does Not Exist?

Problem: Unicorns are one-horned animals.

Existential Statements

We know that unicorns, for example, do not exist. But they do exist in our minds, so what do we do with the word “exist?” Remembering Frege’s claim that “number statements are assertions about concepts,” we need new tools to express that (26ff). They are universal and existential quantifiers, noted thus:

“Unicorns do not exist”

Becomes

– (∃x) Ux

Which Beaney explains to mean, “It is not the case that there are some unicorns.” Therefore, “When we make an existential claim, then, we are not attributing a first-level concept to an object, but a second level concept to a first-level concept” (27).

Applied to theology, this means the ontological argument is unsound. An existential claim is an instantiation of concepts, not objects. God, a first-level concept, can be (and should be) defined as exemplifying all the great-making properties.But is this the same thing as exemplifying existence?

Beaney gives a simpler explanation. If I say “the class of unicorns is a subset of the class of animals,” am I saying unicorns really exist? No, “for are talking about (ultimately) about concepts, not classes” (37). What we mean, phrased in quantificational logic, is

(∀x) (Hx → Ax)

“For all x, if x is a unicorn, then x is an animal.” In other words, anything that falls under the concept unicorn falls under the concept animal.”

Do You Know What I Mean?

Sense and Reference

Hesperus is Phosphorus.

Both of these, one the evening star.and one the morning, refer to the planet Venus, but in different senses.

Evaluation

I am skipping the section on Wittgenstein and language-games, important as it is. That (probably) deserves and has its own book. Rather, I will spend some time analyzing Beaney’s take on the analytic-continental divide.

As students of philosophy today are grudgingly admitting, the divide between analytic and continental styles is not airtight. True, but it is still there. It is certainly the case that analytics aim for precision while continentals tend to reduce things to metaphors and “play.” That said, analytics are often very reluctant to explain modal and symbolic logic.

The next row is certainly accurate. Continentals, most notoriously with John Caputo’s claim that logic was a white man’s enterprise, are skeptical of reason.

The realist/idealist paradigm is odd. If by “realist” Beaney means focused on a real, external world, he is correct. If he means Platonic realism, which I do not think he does, he is incorrect.

The apolitical/political divide is certainly accurate, with exceptions. Bertrand Russell, for example, lobbied for numerous globalist fronts. Continentals, often taking their cues from Marx and French Communist radicals, are certainly more focused on politics.

Conclusion

I knew something about analytic philosophy before reading this book, having even read Frege. Beaney did a find job explaining all the parts I could not understand from Frege.